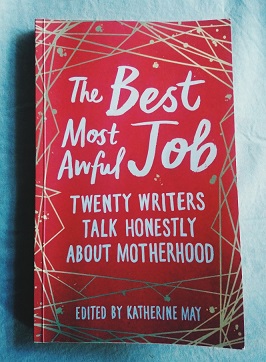

The Best Most Awful Job: Twenty Writers Talk Honestly About Motherhood

The Best Most Awful Job: Twenty Writers Talk Honestly About Motherhood

Edited by Katherine May

A note to the reader.

I read this book and wrote this piece before the world entered a new age and way of life. Before the word pandemic reached our ears and most of the problems were far away enough not to worry. But here we are, separated from our older parents; grandparents, immunity compromised friends and loved ones and now without school, a great weight has been placed on us for how long we do not know. If you are a mother whether you worked from home or not, it is very likely that you have been put in absolute charge of your children’s day to day restricted existence. It is likely that every emotion you have felt connected to motherhood is about to become insurmountably intensified and will have to reach into a well that may already exist or need to get a hold of a good shovel and start digging. We will have to strike a balance, one that may have never been established and therefore now is the time. You may parent alone, you may parent with a disability, with depression or anxiety, and you may be now without the support of a grandparent or older relative. Whatever your circumstance is, there is a mother just like you out there longing to reach out and tell you they understand. This book holds many mothers, many voices and now we are all facing two single battles that connect us; motherhood and isolation.

It is impossible to read these honest accounts of motherhood without vigorously nodding your head; laughing, swearing out loud or hopelessly close to tears. Every one of these emotions are constantly ignited through motherhood. To call it a trippy roller coaster ride is putting it lightly but for most, a ride most of us would jump onto over and over again because there is very little a parent wouldn’t do for their child.

We are thrust into the physiological ramifications of vaginal birth by Leah Hazard, a midwife in What Your Mother Didn’t Tell You. She has the reader immediately wincing at the traumas sustained during birth unmasking scars big and small that remain forever but she does this in the most incredible way. Hazard names each anatomical segment of the vagina and a trauma that that part may experience in a hypnotic, poetic, charismatic and dare I say it, seductive manner. The labelling has a function in itself, it is to “…give women power. To name is to identify and to acknowledge. And in acknowledging these womanly wounds, we open the door to healing.”

Each experience is unique; every mother carries her own history which unfolds into her own mothering experience yet every mother reading these accounts see their own reflection ricocheting back at them. The most prominent theme throughout is that of loneliness. So many women are on the same journey yet loneliness pervades most, particularly in the early months when they suddenly realise they inhabit a different world. Akbar in her essay titled “On the shock of a surprise pregnancy” writes about how she was excitedly preparing herself to re-enter the working world when she found out she was pregnant once more. She describes it as being ‘pushed back into the darkness.’

Mothers enter another realm it seems. They pass through an invisible barrier that separates them, that strips them and makes them invisible. Saima Mir highlights the way in which the patriarchy has created a system designed by men, for men. Then what about the women who are carrying and taking care of their babies and yes, men too take on the main role of caregiver but are they able to assimilate back into society easier than women? Motherhood is an unpaid job, it makes the mother feel unimportant when it is possibly one of the most important jobs yet it leaves women feeling shameful with little self worth when asked the question, “So what do you do?” Mir’s account made me laugh so hard when all the swear words came racing out because we have all been there when you can no longer suppress or internalise.

Amongst accounts of bloody wreckage: invisibility, disability, adoption and single parenthood, there is the question of cultural identity. Which values, stories and beliefs are passed onto the child? Is one more dominant than the other? Huma Qureshi uses the language of food to express cultural identity for food which was to “serve as a reminder of who I was.” Qureshi doesn’t want her children to have to choose one culture over the other but to find a way to marry the two but this in itself is a very difficult concept when one culture is more dominant than the other in certain situations. Then there is the weight of other family members who are fearful for the loss of their own mother tongue as seen in MiMmi Aye’e account. Her children who encompass two ethnicities perceive white as the norm and the brown man in a James Bond movie as the baddie. Her conclusion is dark and full of sadness, that her “Two children wouldn’t fit in, no matter what they did or said, and would be told, like me, to go back to their own country, a country that had not yet visited.”

When children enter your life, a part of the self is laid to the side and put to rest, it may be permanent or it may for a period of time. There may or may not be a period of mourning but with the setting aside of a self, there is the birth of the mother and in this, we are all connected.

-

-

-

-

/ 0 Comments