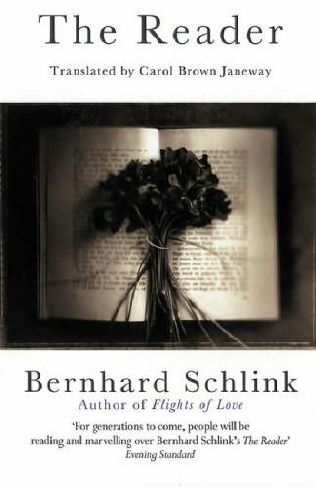

The Reader by Bernhard Schlink

The Reader by Bernhard Schlink

Throughout the book, the concept of ‘guilt’ is prevalent. Guilt is felt by the protagonist, Michael, for failing the older woman that he has fallen in love with, and again, when he finds out that she was an S S Guard. However, there is far more to the guilt that he experiences, there is an unrelenting feeling of guilt as his generation learns about the atrocities of the war, but what is far worst for his generation, is what Schlink talks about in the interview, the knowledge that ones’ own parent was a part of it. As the novel is set in the traditional sense of storytelling, looking back and relaying an account of the past, the concept of memory is entwined with an overwhelming sense of pain, and the pain which Michael experiences is something that he can not let go of, no matter how hard he tries.

“Part One” deals with the young fifteen year old Michael who falls in love with an older woman, Hanna Schmitz, and one is immediately bombarded with a vast amount of sexual imagery. Michael’s voices sounds as though it is coming out from a dark fog, as each word is weighed down with the burden of memory. Schlink is able to capture the emotions and thoughts of a young boy who has reached sexual maturity well, but what he is able to do exceedingly well, is the way in which he describes the possession of a young boy’s soul by an older woman. This possession becomes more obvious as you continue to read on, as Hanna takes on the role as an enchantress and the very embodiment of entrapment. The voice and pace changes in part two as Michael grows up, for a mere moment, it is as though one is reading two separate books, as we step away from Michael’s giddy love, and begin to face the horrors of war. It is in the second part, I feel, where the books’ hook lies, as we are faced with the view of war from a different angle, from the S S Guard.

As a reader with knowledge of the atrocities of WWII, it is unsettling to hear accounts from the other side, especially when we have gotten to know Hanna, not as an S S Guard, but as a lonely woman, yet, when she stands there in court before our eyes, accounting what has happened, and posing the nauseating question to the judge, “What would you have done?” which leaves the judge frozen, we begin to picture a different Hanna. Just like Styron’s Sophie’s Choice, the book is full of choices; good ones, bad ones, and forced ones, and as we read, we take on the role as the judge, deciding upon whose choices were right and whose were a part of something more evil, that is if one believes in ‘evil’ in the first place. This novel provides a unique role when it comes to stories accounting WWII, as we are faced with many ugly truths. This novel is worth picking up, as we are plunged and enveloped in a world that is placed at the centre of pain, and a world that is trying to be forgotten.

-

-

-

-

/ 0 Comments